As an anesthesia provider who specializes in acute surgical pain management, I’ve placed more popliteal-sciatic nerve catheters than I can count. For outpatient foot and ankle surgeries, they’re a bread-and-butter tool—reliable, and effective for patients heading home to recover. But let’s be honest: the continuous infusion model we’ve leaned on for years has its flaws. The reservoir runs dry too soon, and patients are left scrambling, requiring larger doses of opioids for breakthrough pain. A 2022 study published in Anesthesiology, “Basal Infusion versus Automated Boluses and a Delayed Start Timer for ‘Continuous’ Sciatic Nerve Blocks after Ambulatory Foot and Ankle Surgery: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” has influenced my practice—and I’m betting it’ll do the same for you.

The Study: Same Nerve Catheter but with Automated Infusion Parameters

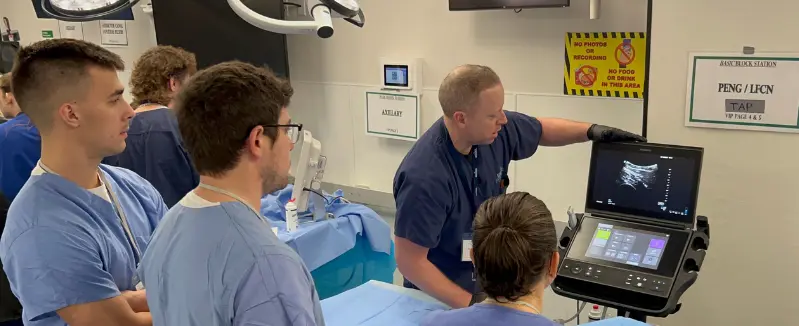

This randomized clinical trial enrolled 70 patients, all having ambulatory foot and ankle procedures, and gave them Ropivacaine 0.5% with 5 to 10 μg/ml epinephrine (20 ml) injected in divided doses through the popliteal-sciatic nerve catheter under direct ultrasound visualization. Then came the division into patient groups:

- Group 1 (Continuous Infusion): Ropivacaine 0.2% at 6 ml/h, started pre-discharge.

- Group 2 (Automated Boluses): Ropivacaine 0.2%, 8 ml boluses every two hours, with a 5-hour delay post-discharge, courtesy of the pump’s programmable timer

Both groups had PCA boluses available (4 ml, 30-minute lockout) as a safety net. We’re talking familiar equipment—same local anesthetics—just a different infusion regimen. The goals of the study? Compare pain scores on postoperative day one and see how long the local anesthetic infusion lasted.

The Data: Numbers That Change Practice

The continuous infusion group posted a median pain score of 3.0 (interquartile range 1.8–4.8) on postoperative day one. Not terrible, but not great—typical of what we can expect when the initial block starts wearing off. The automated bolus group? A median of 0.0 (interquartile range 0.0–3.0). Zero! Adjusted for BMI, the odds ratio was 3.1 (95% CI, 1.2–7.8; p= 0.033)—that’s not just noninferiority; it’s superiority. Patients weren’t just comfortable; they were pain-free.

Then there’s the duration of the infusion. The continuous infusion patients ran out of local anesthetic around 74 hours (interquartile range 57–80), which makes sense when you provide patients with a standard 400–500 ml reservoir at 6 ml/h. The automated bolus group stretched the duration to 119 hours (interquartile range 109–125)—an extra two days. That’s 47 hours more (95% CI, 38–55) of duration, all because the automated bolus approach uses less local anesthetic over time than the traditional basal infusion setup.

Why It’s a Win for Anesthesia Providers

From the anesthesia provider’s perspective, this is a no-brainer. The setup’s the same—thread the catheter, secure it, and hook up the pump. The only difference? Make sure you are using an electronic infusion pump instead of an elastomeric pump: swap the basal rate for automated boluses and set a delay. It’s not rocket science; it’s a tweak. But the payoff? Patients aren’t calling at 2 a.m. because their pumps are empty and they are in pain. Fewer opioids are required for breakthrough pain. Better satisfaction scores. And honestly, as an anesthesia provider who is passionate about acute pain management, it feels good to send someone home with a plan that’s this dialed in.

The delay timer is an important piece here. That 5-hour delay syncs with when the initial block wanes and surgical pain creeps in—genius. And the boluses? They happen every 2 hours, instead of the slow continuous infusion we’ve been used to in our practice. Less total volume, better spread, longer duration—it’s pharmacokinetics working in our favor.

The Catch—and the Opportunity

Sure, there’s a learning curve. Not every pump has a delay function, your practice may need to seek out a different pump vendor to meet your needs. You and your staff will need to know how to program it. Patient education is key too—explain the delay so they don’t panic when the pump’s quiet for a few hours. But these are speed bumps, not roadblocks. The evidence is too strong to ignore.

The Bigger Picture for Your Regional Anesthesia Practice

This isn’t just about foot and ankle cases. It’s a proof of concept. Could you tweak the adductor canal blocks for the knees? Interscalene blocks for shoulders? The idea of trading continuous flow for timed boluses with delays—could ripple across your regional anesthesia practice. It’s a chance to refine your craft, lean on tech, and keep patients ahead of the pain curve.

Our Practice Change: Automated Infusion Pumps for the Win

In our practice, we placed nearly 1,500 nerve catheters annually for patients going home after surgeries. We became early adopters of automated infusion pumps. We made the switch from elastomeric infusion pumps to an electronic infusion pump that allowed for automated boluses and delayed infusion starts. Our Goal? To prolong infusion times as long as possible for our patients. These changes led to clinically meaningful outcomes for our patients and a sense of pride in our acute pain program.

Final Thoughts

I’ve always trusted popliteal-sciatic nerve catheters, and this study provides us with evidence-based knowledge about how we deliver our local anesthetics. Automated boluses with a delayed start aren’t just an alternative—they’re better. More effective analgesia, longer coverage, and similar workflow. It’s the kind of data that makes you want to grab a pump and start programming. For any anesthesia provider out there, this is a wake-up call: our old standby just got an upgrade, and our patients are going to thank us for it.

Check out the full study for the nitty-gritty—it’s worth the read if you’re as passionate about regional anesthesia as I am!

Reference:

Finneran, John J., Engy T. Said, Brian P. Curran, Matthew W. Swisher, Jessica R. Black, Rodney A. Gabriel, Jacklynn F. Sztain et al. “Basal infusion versus automated boluses and a delayed start timer for “continuous” sciatic nerve blocks after ambulatory foot and ankle surgery: a randomized clinical trial.” Anesthesiology 136, no. 6 (2022): 970-982.

https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/wk/aln/2022/00000136/00000006/art00020

John Edwards

DNAP, CRNA

Lexington, KY.